[This article was originally published on May 27, 2018 at The Warden Post.]

Of all the ideas that hold sway over human consciousness perhaps none is so powerful as the idea of home. Home is something much more than just a place to lay down one’s head; it is a sense of rootedness, a nostalgia towards places, things, experiences and memories that have had a real and fundamental impact on one’s development as a human being.

Lance Kennedy’s The City Called to Him is about a man, known only as the Wanderer, having returned to the city of his youth only to find it profoundly changed. The City, once a vibrant place filled with activity and life, is now a dreary, desolate corpse-stricken charnel-house ruled over by a sorceress known only as the Mother. The Mother ascended to the throne of the City after first gaining the trust of it's Lord and then betraying him using dark magic to open a rift in reality, summoning forth all manner of daemons and eldritch abominations who proceeded to empty the City of all human life.

This book by Mr. Kennedy is by no means a long work, with myself having finished it in just one afternoon. Despite its short length, the book itself is filled to the brim with allegory. The City called to Him reads like a dark fairy tale and probes the crevices of the human subconscious, presenting us with a parable of Mans desire to understand himself and to recover those long-lost experiences which have been archived away in the distant past, made unreachable by the passing of time.

The story opens with the Wanderer returning home after traversing the wastelands far from his native soil after nineteen long years. From the distance, he can see the grim glow of beacons emanating from behind the City’s walls. As he travels down from his perch alongside the cliff-face of a mountain, he finds all around him to be gray and desolate. The farms and homesteads outside the City lie ruined and abandoned, with no signs of life anywhere except for the occasional rat.

He eventually finds himself at the entrance of a ruined hovel and discovers the skeletons of a mother and child, ropes around their necks implying they had both committed suicide to spare themselves from the horrific death that would have awaited them at the hands of the Mother’s daemonic warriors. Scrawled in blood on the walls of the domicile is a warning, announcing to any future traveler to beware of the Mother and proclaiming none but the dead dwell inside the City.

It is heavily implied that the two corpses belonged to the Wanderer’s own wife and child, whom he had left behind to pursue his journey to the lands beyond the City. After burying the two skeletons in shallow graves, he presses onward toward the gates of the City. From a distance the Wanderer can make out the mighty walls and parapets of the City as well as the massive citadel which towers over the central plaza, built upon the rocky outcropping of a hill. Instead of the regal banners fluttering proudly overhead, the citadel’s tower is now ornamented with a garland of human skulls.

Still some miles from the city gates, the Wanderer makes camp for the night in the hollow of a wood. Dozing off next to the warm glow of the fire, he drifts into a deep dream. In this dream-state, he can feel the very gaze of the ancient woods bearing down upon him. Frightened, the Wanderer asks the trees if they are afraid of him. The trees reply that they are, remembering that when the City was still filled with life, how the people of the fields would fell their trunks for their homes and fuel and expressed their gratitude towards the Mother for having rid them of the human threat.

Thereupon, they begin pressing the man about how now that his fire is out, he will eventually need more branches for the flames. The Wanderer reminds the ancient wood that his people took no more than what they needed and that their sacrifice had ensured that they had homes and shelter, and in the process, had cleared away all the bramble and undergrowth that had prevented the trees from growing higher towards the sun. The trees, reflecting on their short sightedness, agree to renew the old pact between forest and men and allow the Wanderer to gather loose and rotting branches for his fire, allowing him to pass night away in peace.

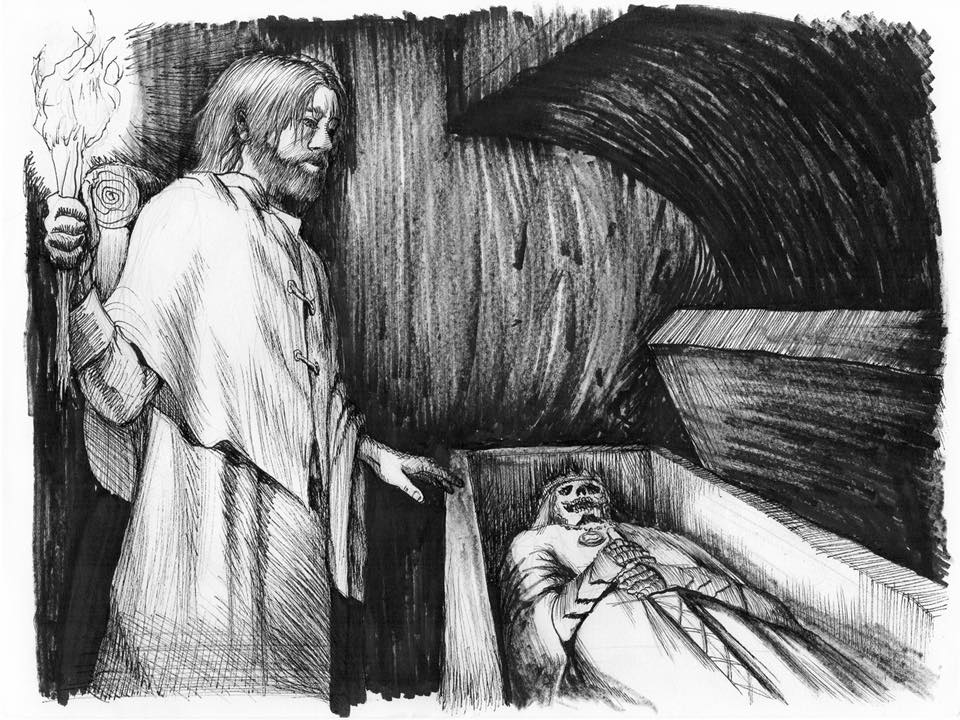

Along the stretch of road that led to gates of the City, the Wanderer notices the half-spherical forms of mounds rising steadily from the landscape in the distance. Noticing the unnatural shape of the hillocks, he ascends the nearest mound and finds a stone portal that leads into the pitch-black innards of the barrow. After constructing a make-shift torch, the Wanderer descends into the mound, crouching his way through the darkness and eventually finding himself in a large chamber, riddled with treasure, beneath the center of the kurgan. Here, the Wanderer finds himself presented before a stone sarcophagus, it’s surface covered in runes.

The Wanderer pushes the lid of the sarcophagus aside to find a skeleton, draped in regal attire gripping a sword to its breast; heavy pendant adorning its neck. For a moment, the man is silent and whispers an apology to the remains of whom we now know to be the former Lord of the City. The Wanderer relieves the skeleton of its sword and pendant, knowing he will need both for the trials ahead.

Finally arriving at the gates of the City, the Wanderer finds himself finds himself before the great guardhouse built into its main gate. The gatehouse is covered in the same alien, presumably daemonic, runes that adorned the dead Lord’s sarcophagus. The Wanderer moves in closer to inspect them, tracing the glyphs with his fingers and into woodgrain.

Our hero is suddenly attacked by a hideous green form, inhuman hands grabbing his neck through a portal through the guardhouse. Using the sword he had taken from the tomb, the Wanderer beheads the creature in one fell swoop. Stunned but not deterred, the Wanderer presses onward knowing that far worse horrors await him.

In the dim light of the gatehouse, the Wanderer sidesteps the rotting remains of both humans and vermin, victims of the creature whom our hero had slain. The powerful stench of death has now become overwhelming. The entrance is flanked by colonnades yet with the drawbridge to the City raised, the Wanderer can progress no further. The task remains to find the drawing mechanism to lower the bridge and by relying upon the memories of his youth-- when he would venture the dark and shadowy corners of the City-- he recalls where the room might be. As he rounds the corner to the room he is immediately seized by innumerable arms and lifted upwards as his weapons and gear are stripped from him. He is passed hand-to-hand by the shadowy tendrils as he is carried further into the darkness, completely vulnerable and unable to do anything but scream.

Just as suddenly as he was pulled into the darkness, the Wanderer finds himself in a room with no forms of entrance or exit, groin-vaulted ceiling above him, bookshelves filled with arcane texts to his side and the figures of an aged man and five children before his eyes. After a brief silence, the Wanderer asks who the man is and how he came to be in such a place. This provokes a smile from the aged mage who explains that he is “the remnant of the city of men...” he further calms the traveler’s nerves by explaining that he is not an enemy and that he equipment and valuables are neatly hung on the wall behind him.

The enchanter then enquires who the Wanderer might be and how he came to find himself in the City of the Dead. The Wanderer explains that he was once a child of the City but left home to fill a yearning in his heart that he could no longer ignore, even though it meant leaving everyone and everything in his previous life behind. After nineteen years of meditation in eastern deserts and empty plains, he returned home only to find the city of his youth in ruins.

Seemingly satisfied with this answer, the old mage begins a story where he describes his previous life as the Chief Astronomer to the Lord of the City. One day, a wise woman came to the gates of the City and awed its people and their Lord with amazing spectacles and displays of magic and divination. Unable to replicate the miracles and forecasts, the Lord had the Chief Astronomer relieved of his position and banished from the City, raising the seeress up as his vizier.

The decision proved to be fatal, for both the Lord and his city. The wise woman, as it would turn out, was the Mother of the Dead and through the invocation of dark magic spells, caused the City to pulse with unnatural and eldritch energies unleashing a portal which seemed to tear through the fabric of reality itself. From the gaping maw of the portal emerged all manner of unspeakable horrors which ravaged all life, leaving the City empty save only for daemons and corpses.

The Mage describes how he had taken refuge with a family of farmers on the outskirts of the City. Unfortunately, when word had come about the City’s destruction, it came far too late. The farmer and his wife were killed by the walking horrors that stalked the ruined streets of the Mother’s prize, but the old wizard and the couple’s five children had found shelter in the consistory of the Mage’s arcane Order. There they remained for nineteen years, shielded by the effects of curious magic and unaffected by the passage of time.

The Mage then explains that in one last act of mockery, the Mother commanded her monsters to build burial mounds in the custom of Men, stowing away all the treasures and relics of the City with its now-dead denizens. All memory that life had even existed in these ruined halls had been put out like a dwindling flame; her victory complete and her rule unchallenged. The old magus then tells the Wanderer that he could sense, however, that the City’s salvation was at hand, that somehow a presence was coming to liberate this corpse-city from the Mother’s rule. It was it that time that the Mage and the children had been preparing for the Wanderer’s eventual return.

While explaining to the Wanderer that both sword and medallion are ancient artifacts imbuing the wearer with unnatural courage and strength, he outfits the returning hero with armor, helm and shield. The Wanderer, knowing that he cannot face the Mother’s untold host of minions alone, inquires of the Mage how he can possibly defeat her and her armies. The Mage informs our hero that he has come into possession of a spell that will greatly aid them, all it requires is a drop of blood from one with a righteous heart. With the flick of his wrist the Mage cuts the Wanderer’s finger and mixes the blood into the strange contents of a vial at his side before emptying the contents on the ground. For a moment, nothing. Then suddenly the whole earth begins to shake. Silent as death, the undead warriors of the City, victims of the Mother’s designs, begin emerging from their tombs and rally to the Wanderer’s standard. An army, acquired through horrible necromancy and bound to its commander by life’s blood.

With the assault on the gatehouse underway, the reluctant general and his army of the dead descend upon the walls of the City. There they are met by the stones and arrows loosed upon them by the Mother’s inhuman cohorts. Just as the gatehouse seems to fall to the army of the dead, twelve hooded figures descend upon the corpse-soldiers. No matter how many blows and arrows land upon the hooded figures, they seem to take no damage. It is then the figures cast of their cloaks and reveal their true forms, not of flesh but dark fog or mist.

From the sky the aged mage calls down a blazing inferno, engulfing the ghostly wraiths in a raging firestorm. With victory just within reach, the Mage is suddenly struck by a lone arrow, launched over the gate by an unseen foe. The Wanderer catches the Mage in his arms before gently lowering him to the ground. With his dying breath the old magus tells the Wanderer that he will be the salvation of the City and to press onward as well as passing with him a cryptic message, explaining that “When the time comes you will know that the secret lies within.”

The Mage’s body is carried away by the five children back to the sanctum. Meanwhile, the Wanderer and his undead army rally together for one last push through the gate. Victory is theirs when the iron bars and wooden doors give way to the steel point of their battering ram. The Mother’s vanguard is eventually overwhelmed and the greater part of the City is reclaimed by the dead.

Soon after their victory they are met by an emissary of the Mother, an obese plague-ridden monster covered from head to toe with sores and buboes, carried aloft on a liter borne by a party of malformed entities. Despite the obvious defeat of the Mother’s forces, the plague-ridden emissary seems almost jovial, taking a keen interest in the Wanderer’s living, uncorrupted body. The Mother’s emissary bears a message: surrender and live or resist and be destroyed. After a long silence on the part of the Wanderer, the plague-bearer orders his host to withdraw in obvious contempt.

The army of the Dead led by the Wanderer then prepare for the final assault on the citadel. They are met by another force of daemons led by a ghastly rider, bleeding out of every conceivable orifice and mounted upon a pale horse. The rider makes the same demands to the host of the undead that the previous messenger had: surrender or die. Thus, began the final assault on the citadel.

After a fierce battle, the forces of the undead led by their living champion are victorious. The bloody rider is forced to retreat into the safety of the citadel. The citadel itself is perched firmly upon the rocky outcroppings of a hill in the center of the City. Only one road exists which leads either in or out. The entrance to the stronghold is guarded by a massive stone gate. Even with their battering ram destroyed, the host of undead soldiers press on, led personally from the front by their living general. Such bravado on the part of the Wanderer is soon wasted as a trap had been prepared; a metal grate gives way underneath his feet and he falls into the dark, labyrinthine depths of the City’s underbelly.

Bringing himself back up onto his feet, the Wanderer realizes he has fallen into the City’s ancient sewer system. Unharmed, but bitter over his failure, the Wanderer gropes around in darkness, looking for a wall he can use help guide his way. As he walks amidst the dried putrescence of City’s sewers, he notices a small light growing larger and ever closer until he can make out the image of five small forms walking towards him. The Mage’s children have appeared to escort him through the darkness to the Mother’s tower. They can lead the way, but can go no further. The final battle must be fought between the him alone.

Through the bowels of the City the children bring our hero to an ancient service door used in bygone days to reach the sewers from the Citadel’s heights. A gentle nudge pushes the door open and a voice from the darkness bids the Wanderer welcome, urging him to come. The Wanderer instructs the children to return to the safety of his army while he prepares to confront the Mother and her evil at last.

Ascending upwards from the rusted sewer pumps, water pipes and septic systems our hero finds himself in an unusually lavish room. All around him he finds luxury and exuberance: ornate chairs and couches, ferns and exotic plants, marbles columns and statues, gilded niceties, bejeweled objects; the room itself smelling of sickly sweet incense.

On the far-side of the room is an elevated dais. The Wanderer hears a creaking noise, he looks up and finds a platform descending to the pulpit below. Determined to find the source of the voice beckoning to him, he mounts the platform, pulls the lever to his side and begins his ascension some two-hundred feet into the air.

Rising to the top of the tower, the Wanderer is greeted by a figure. To his shock, it is not the figure of a daemon or a crooked hag-witch but a beautiful woman in a white gown laced with silver. He stares her down, his sword at the ready much to the amusement of the sorceress who invites him to sit and converse with her in the comfort of her chamber. Suspicious, but accepting her invitation, the Wander takes a seat opposite her and the two silently stare each other down, searching one another’s gazes.

The Wanderer breaks the silence, “What happened to my city?” he asks. A few more moments of silence before the Mother replies in turn. She starts from the beginning, reiterating the same tale that the old mage had told the Wanderer when he had first set foot into the tomb-city. She notes, however, one important detail, namely the coincidence that the day the Wanderer began his journey eastward was the day she arrived at the City’s steps. She then tells the Wanderer straightaway that they are in fact the same person; that the Wanderer’s attempts to leave everything behind, his past, his people, history and Lord was the day that evil entered him.

Inflamed by the pain of such a revelation, the Wanderer draws his sword and impales the Mother on his blade. Immediately, the Mother’s form begins to shimmer and change. The Wanderer now stands face to face, not with the Mother, but a mirror image of himself. Stunned, the Wanderer tries to release his grip from his sword but is unable to do so. It seems he has now been caught within the pull of powerful, unknown magic.

The Wanderer and his double begin to slowly rise from the floor; a strange light engulfs the pair as they ascend higher and higher towards the roof of the tower, rotating around one another like binary stars. They orbit one another at incredible speed, breaking through the roof of the tower, soaring high into the sky until the human star explodes in a display of white light amidst the red and purple of twilight. The undead army looks on in wonder through hollow sockets.

A thunderous roar shakes the ground beneath them and a sword and pendant clang loudly as they hit the cobblestone at the entrance of the City’s keep, their former owner nowhere to be seen. In amazement, the soldiers massed outside the stronghold find that life has been returned to their bodies. Where once ragged putrescent skin, browned by the passing of years clung loosely to bone, they find instead that muscle and sinew now pulse under soft pink flesh; new blood flushing their checks a bright red.

A joyous shout erupts from the throng as the long-sought victory has now been won, the City has been reclaimed by life. Wives and children are reunited with husbands and fathers and a lone figure walks over to the sword and medallion where they lay settled before the tower’s steps. The figure, now revealed to be the Lord returned to life, calls out to his people, prostrates himself before them and asks forgiveness for his folly. His people do so, shouting in unison their unanimous approval. The Lord takes his place again, now, as King.

Four men, tall and strong-armed, and a woman, unsurpassed in beauty, are lovingly embraced by a woman and her husband. The children under the wizard’s stead are now reunited with their parents. Meanwhile the aged Mage takes in the victory nineteen long years in the making. He is embraced by the King who asks forgiveness of the magus for his foolishness. He accepts, provided on the condition that the five children are rewarded by being made members of his ancient Order. The King agrees.

The City and its people are restored to life, the King to his throne and the Mage at his side. The road ahead would be long but all were confident that the City would be rebuilt, this time far greater than ever before.

***

At the beginning of this review I described this book as a dark parable. Indeed, the allegory which Mr. Kennedy presents us with examines the depths of the human subconscious. The figure of the Wanderer is taken to be the archetypal Hero-figure central to all human myths and stories. Moreover, I would even suggest that the Wanderer represents the Evolian non-conditioned “I” or the Jungian conception of the “Self.”

From a Traditionalist perspective, the non-conditioned “I” finds it’s synonymy in the Hindu conception of the Atman, the unchanging, transcendent non-human aspect usually held to be identical with the Soul. The Atman is held to be one’s “true self” and is considered to both separate and distinct from the ego, viz., the conditioned “I.”

The City in this story represents the plane of both conscious and unconscious experience, usually described as the psyche. The City is the vessel representing the innermost portion of the mind which holds the Wanderer’s thoughts, experiences, memories, desires and inclinations of both waking life and that repressed in the face of personal trauma. The City can also be analogous to the ego, viz., the conditioned “I” which represents the Self which we are accustomed to project through social conditioning; through our belonging to a certain ethnicity and culture, in a certain country or region and at a certain place in time which was not of our choosing.

Acculturalization and socialization are facts of human existence. One might be born a North American in the great metropolises of New York and Los Angeles or in a simple yurt on the steppes of Mongolia; it makes no difference regarding our conditioned identities. It would be as fruitless to unlearn our conditioning and experiences as a modern Westerner as it would be to unlearn our acculturalization had we’d been born as Trobriand Islanders. Man, as a fact of his existence, will always have a conditioned identity from which he cannot escape.

This, however, is precisely what the Wanderer attempts to do. The Wanderer turns his back on his home, his family and indeed the whole of the City itself: it’s history and people, it’s stories, culture-life, ancestral totems and myths. Everything that made the Wanderer who he is as a person is abandoned as he makes efforts to “discover” himself amongst the desolation of a foreign land.

The Wanderer, like all of us, is eventually forced to return home, to retreat inward during a moment of crisis and confront that which was assumed to have been sealed away in the deepest crevasses of our unconscious mind. The City, representing the ego, is now discovered to be completely changed from whence we left it. Take for example of how in our youth we might have had dreams of being an astronaut or growing up to write the next Great American Novel.

Overtime, most of us eventually lose sight of the dreams of our past when forced to deal with the realities of early adulthood. It might happen that one night, after long day at work, we sit down and mediate in the few moments of peace allotted to us in the evening, finding ourselves deeply dissatisfied with the way our lives have turned out; wishing that it had happened some other way. More tragically, we might think to ourselves that our “real lives” haven’t started yet, that success and happiness are just right around the corner in the always-not-yet-here. Thus, begins the “Dark Night of the Soul” as described by Saint John of the Cross some four centuries prior.

The Wanderer finds himself at the outskirts of the City, representing the limits of waking consciousness before taking his first fateful steps past its towering walls, deeper into the innermost and unexplored recesses of the unconscious mind. After many trials and aided by the guidance of the Mage– an interesting figure whom we can presume to represent the inner voice of our mind, the one which nags at us to confront the truth about ourselves, no matter how unpleasant or difficult—we find ourselves at the base of the citadel. With retreat no longer an option, we have only one path remaining to us: to ascend.

There, waiting for us in the highest tower in the citadels keep is the Mother, the dark Anima casting its ever-present shadow over the totality of our unconscious mind. The Anima, a psychological term forwarded by Jung, is said to the unconscious feminine qualities that exist in every man which, when developed, allow him to open-up to emotionality, creativity and other intuitive processes. The anima is also said to manifest itself in dreams and, during our waking consciousness, how we interact with women in both our public and private lives.

This reveals to us at last the puzzling message the old wizard gave the Wanderer with his dying breath, “When the time comes you will know that the secret lies within.” By undergoing ego-death and uniting both masculine and feminine energies to his non-conditioned existence, he achieves moksha—the final liberation from naturalistic existence that he has for so long sought. The Wanderer, again, representing the non-conditioned “I,” has finally transcended the profane, individual qualities of conditioned life and oriented himself firmly towards pure Being. Thus, the Wanderer has at last achieved what has been described in the Eastern Church as theoria, the union of the non-conditioned Self with the inner wholeness of the Divine.

Lance Kennedy has given us a true work of literature whose importance will not be lost on those seeking to grasp a deeper understanding of the human mind and all its peculiarities. The Wanderer for us should be as a new Odysseus, come at last after so many years to liberate his home from the evils that have befallen it. The City Called to Him is an exceptional light novel whom I recommend to those who have an interest in fantasy as well anyone interested in psychology and the human condition.